Alert 04.18.25

Alert

Presidential Memo Directs Immediate Repeal of Regulations Without Public Notice and Comment

The memorandum directs federal agencies to reassess and potentially rescind regulations deemed inconsistent with 10 recent Supreme Court rulings.

Alert

Takeaways

04.23.25

Continuing with the Trump administration’s deregulatory agenda, the White House issued a Presidential Memorandum on April 9 titled Directing the Appeal of Unlawful Regulations. It instructs executive agencies to repeal regulations that, in the administration’s view, are “unlawful” in light of 10 recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions. The directive builds on Executive Order 14219 and the broader “Department of Government Efficiency” initiative and calls for a sweeping review and repeal process.

Most notably, the memorandum encourages agencies to invoke the “good cause” exception under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) to bypass notice-and-comment rulemaking, stating that public participation is “unnecessary” or “contrary to the public interest” where repeal is compelled by the cited Supreme Court precedent.

Ten Supreme Court Decisions at the Core

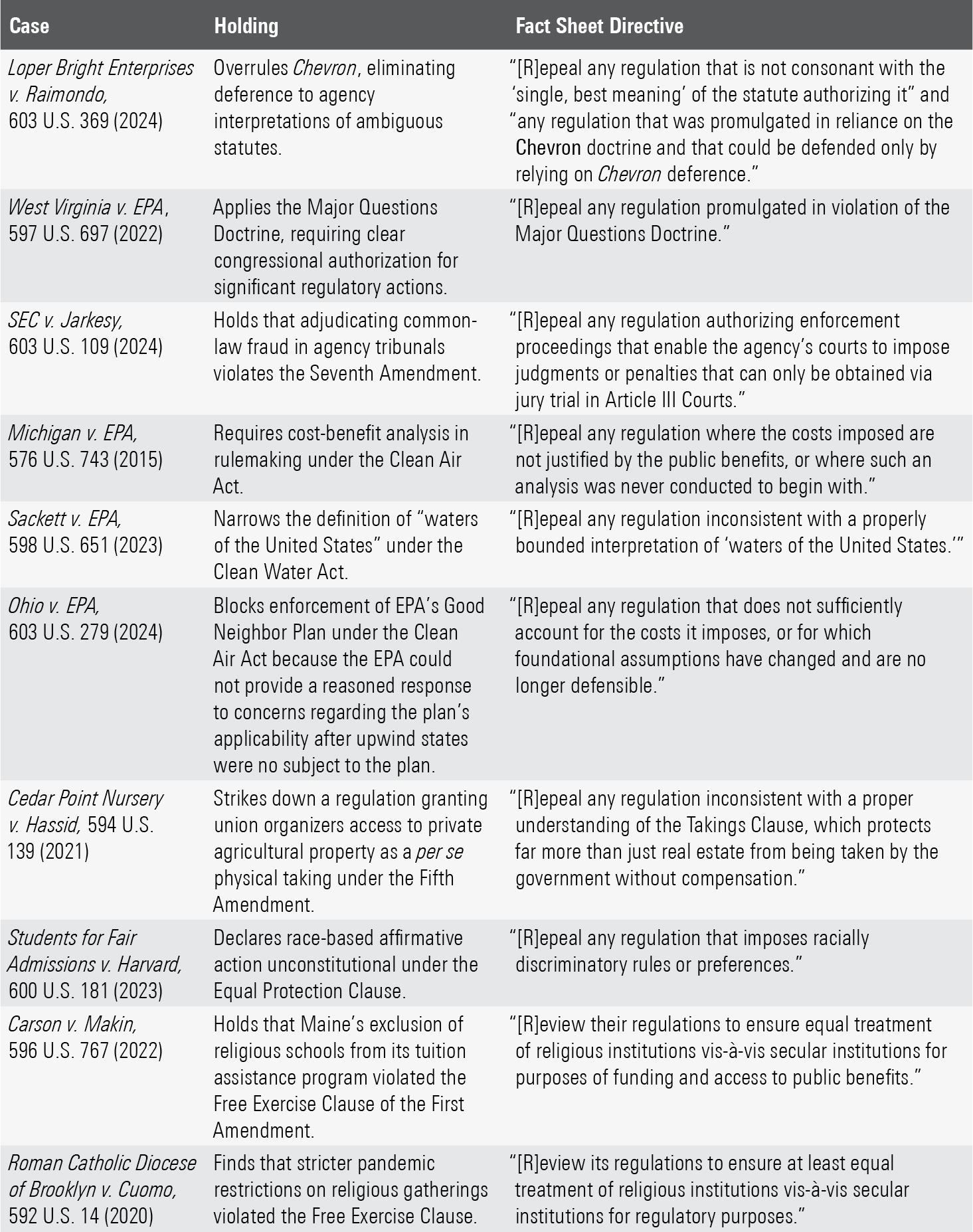

The memorandum and accompanying fact sheet identify 10 recent Supreme Court decisions that have effectuated material shifts in administrative or constitutional law as the basis for repealing existing regulations. The fact sheet directs agencies to repeal or revise existing regulations in accordance with these cases:

APA Rulemaking Requirements and the “Good Cause” Exception

The APA generally requires agencies to follow notice-and-comment procedures for substantive regulatory changes, including repeals. This process is a cornerstone of administrative law, promoting transparency and allowing the public to participate in shaping federal regulations. Notice-and-comment rulemaking typically begins with the publication of a proposed rule in the Federal Register, followed by a public comment period during which individuals, organizations and other stakeholders may submit input. The agency then reviews the comments, makes any necessary revisions and publishes a final rule.

The APA permits agencies to bypass these procedures when the “good cause” exception applies, i.e., when public input is “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” 5 U.S.C. § 553(b)(3)(B). Federal courts have long held that this exception must be “narrowly construed and only reluctantly countenanced.” Mack Trucks, Inc. v. EPA, 682 F.3d 87, 93 (D.C. Cir. 2012). In practice, courts have applied the exception in few circumstances:

- “Impracticable”

- Emergencies: National security threats or public health crises requiring immediate action.

- Deadlines: Where notice and comment would prevent compliance with a statutory or judicial deadline.

- “Unnecessary”

- Technical Corrections: Non-substantive changes unlikely to draw public concern.

- No Discretion: Where the agency is executing a clear statutory mandate with no policymaking judgment.

- “Contrary to the Public Interest”

- Harm from Delay: Where time lost to comment periods would cause significant public harm.

- Preventing Circumvention: Avoiding preemptive regulatory evasion.

- Market Disruption: Preventing economic manipulation or instability resulting from advance notice.

The April 9 memorandum contends that the good-cause standard is categorically met for regulations deemed “facially unlawful” under the cited Supreme Court cases, making public comment both unnecessary and contrary to the public interest.

Implications and Legal Risks

It remains to be seen how executive agencies, including the EPA, plan to implement the executive memorandum. On its face, it opens the door for sweeping agency actions aimed at deregulation, especially given the enumeration of the Loper Bright decision as one of the core Supreme Court cases. The issue of deference to Agency interpretations of the law is raised in an overwhelming majority of APA rulemaking challenges. From an environmental standpoint, this stands to enable EPA to overturn a range of controversial recent regulations, including, among others, the recent hazardous substance designations and maximum contaminant levels established for PFAS.

If agencies implement the memo’s direction and repeal regulations without public input, litigation is virtually assured. Advocacy groups have already announced plans to challenge the approach. Critics argue that the administration may be overreaching—particularly by attempting to apply decisions like Loper Bright retroactively, citing the Supreme Court’s express statement that its holding is prospective.

Litigation may not proceed uniformly, given the lack of consensus among federal courts on how to evaluate good-cause claims:

- The D.C. and Second Circuits apply de novo review, independently determining whether the statutory criteria are satisfied.

- The Fifth, Eighth, and Eleventh Circuits apply arbitrary and capricious review, deferring to agency reasoning if it appears reasonable and supported by the record.

- The First, Third, Fourth, Sixth, Seventh, Ninth and Tenth Circuits have not adopted a clear or consistent standard, often applying mixed or fact-specific approaches.

This divergence increases the risk of inconsistent outcomes across jurisdictions. However, if challenges to the same regulatory repeal are filed in multiple circuits, the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation may consolidate them—potentially assigning the matter to the D.C. Circuit, where de novo review would apply.

Conclusion

Agencies are being directed to swiftly repeal a broad portfolio of regulations the Trump administration deems inconsistent with recent Supreme Court rulings without following the APA’s notice-and-comment process on the basis that “good cause” obviates it. Whether and to what extent that approach will withstand judicial scrutiny will almost certainly be tested and remains to be seen. Given a varying patchwork of “good cause” jurisprudence, the results may well be mixed.

This area of administrative law—and its implications for environmental regulation—is evolving quickly and is likely to remain a focus for courts, agencies and regulated entities in the coming months. Pillsbury attorneys will continue to closely monitor these developments and provide updates as they unfold.