Alert 01.27.25

Alert

New ASTM Standard Aims to Facilitate Assessing Climate Risk and Resilience Considerations

Alert

Takeaways

01.28.25

Owners, lenders and investors in real property have long relied on ASTM E 1527-21, a product of ASTM International, in connection with Phase I Environmental Site Assessments. This product is used to establish that “all appropriate inquiries,” as defined at 42 CFR § 9601(35)(B) and 40 CFR § 312.20(a), have been met in connection with a property. As a matter of law, the performance of an ASTM-compliant Phase I ESA enables prospective purchasers and lessees to satisfy one of the criteria for statutory protections against liability for pre-existing environmental conditions under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act. It also constitutes an indicia that appropriate environmental due diligence has been performed regarding the property.

In recent years, growing concern has arisen that climate change and other natural hazards, beyond environmental contamination, must be taken into account in the evaluation of real property transactions. However, to date, no consensus exists as to which risks, if any, should be taken into account or on the data and metrics for identification and evaluation of these risks.

ASTM International recently announced the publication of a new standard: the ASTM E 3429-24 Standard Guide for Property Resilience Assessments (PRAs) (referred to as the “New Standard” or “Standard”). The New Standard is intended for use by parties, such as real estate investors, owners, operators, lenders and insurers, interested in ascertaining the potential risk posed by natural hazards, including those made more extreme by climate change, for a given property. The New Standard contemplates use of PRAs as part of the due diligence associated with real estate transactions, investment and lending decisions, site planning and development, portfolio risk analysis, property management, capital planning, and climate risk analysis and reporting. The New Standard establishes a generalized and systematic approach for conducting PRAs. Unlike ASTM E 1527-21, the New Standard is not directly linked to a statutory provision and purports to evaluate conditions that may be more speculative in nature than those investigated in an environmental audit.

Why Did ASTM Issue the New Standard?

ASTM issued the New Standard to provide an overview of a generalized, systematic approach for conducting a PRA that identifies hazards,[1] evaluates risk,[2] and if necessary, identifies measures to enhance resilience[3] for a specific property. Importantly, ASTM asserts that the New Standard is not intended to provide a certification of a property as resilient or to characterize a property as compliant with the Standard, but rather to outline a flexible approach to facilitate informed decisions at the property level.

According to ASTM, the New Standard is “intended to complement existing property decision-making processes involving existing ASTM standards,” including the Phase I Environmental Site Assessment standard (ASTM E 1527) and the Property Condition Assessment standard (ASTM E 2018). By linking the New Standard with these existing standards, ASTM contemplates it will become a standard part of the due diligence process. However, there is no expectation that the New Standard and ASTM E 2018 are necessary to qualify for bona fide prospective purchaser status.

Who Performs the New Standard?

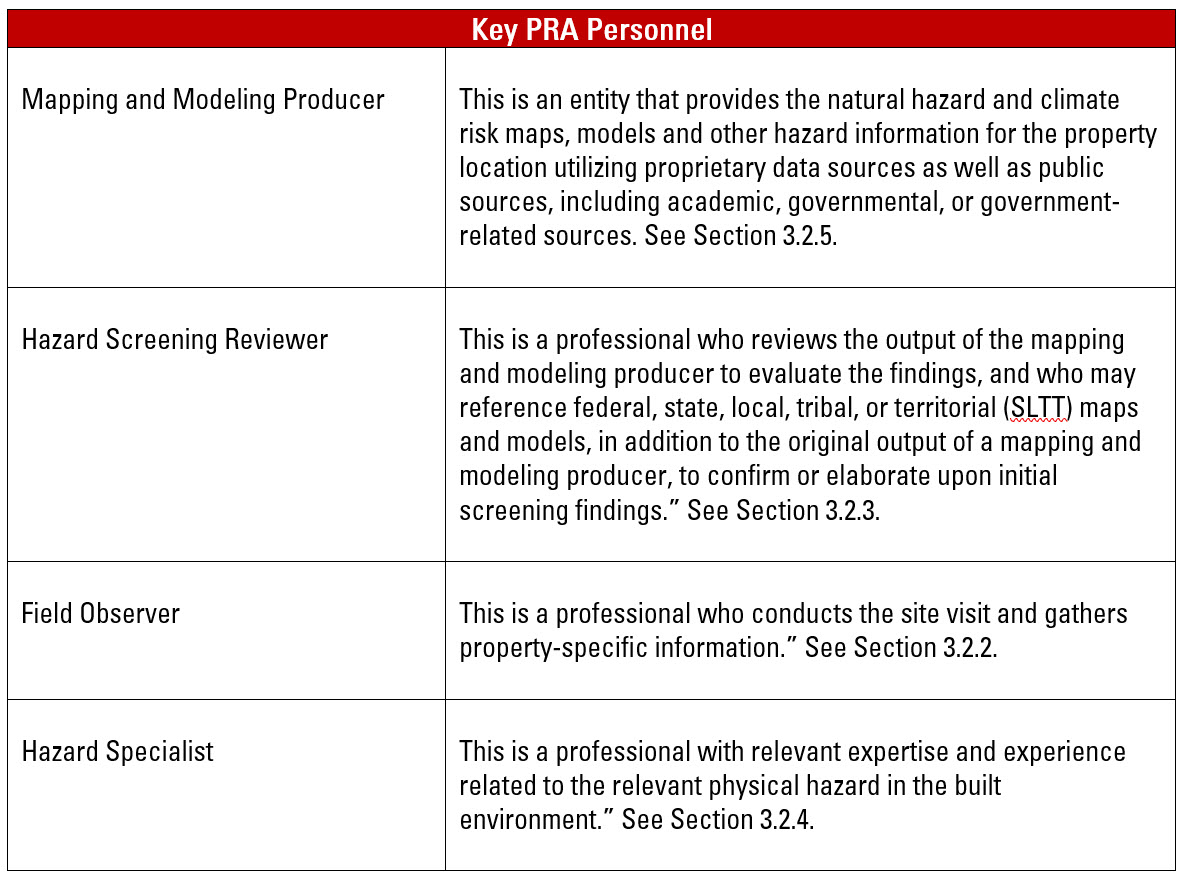

PRAs are performed by a team of consultants, led by a “PRA professional,” who must hold a professional designation in architecture, engineering or science, along with a minimum of three to five years of appropriate experience in building performance, natural hazard mitigation or building resilience. Additional PRA consultants include:

The PRA professional may simultaneously serve in any or all of these roles, provided he or she identifies themselves for each such role in the PRA.

What Are the Substantive Requirements of a PRA?

An ASTM-compliant PRA comprises up to three stages, which may be performed sequentially. A party may request only a Stage 1 PRA or the entire process, from Stage 1 through Stage 3. Similarly, a party may seek a PRA for a single building, multiple buildings or a portfolio of properties.

Stage 1: Hazard Identification. The first step is to identify the natural hazards that are likely to affect the target property by utilizing publicly or commercially available natural hazard and climate data or models, as screened against other resources, including national, local or regional hazard maps, flood maps and FEMA’s National Risk Index Map. The Stage 1 findings must identify a list of hazards of concern (e.g., flood, wildfire, hurricane), a (qualitative or quantitative) indication regarding frequency and severity of each hazard, and a qualitative overall hazard ranking (e.g., low, medium-low, medium, medium-high, high).

Stage 2: Risk Evaluation. This Stage provides a risk evaluation, as well as an assessment of the capacity of the target property to prepare for, adapt to, withstand and recover from the hazards of concern identified in Stage 1. The risk evaluation must convey qualitative and quantitative findings regarding potential impacts on safety, damage, functional recovery time and community resilience. For example, safety impacts can be expressed either in a qualitative hierarchy (e.g., low, medium, high) or quantitatively (e.g., number of injuries, hospitalizations, fatalities for a given hazard level). Damage can be expressed as a numeric result (such as a monetary value or ratio), alphabetic scale, color code, or other type of multi-level qualitative system.

Stage 3: Resilience Measures. This final stage utilizes the information gathered in Stages 1 and 2 to identify, evaluate and prioritize measures that can be employed to improve resilience of the target property. Each measure is evaluated and prioritized based on several criteria, including, among others, expected cost, feasibility of implementation, expected timing of implementation, and probability and consequence of failure. Examples of possible resilience measures include things like installing a flood barrier, relocating critical equipment, increasing energy efficiency, and installing hurricane related glass and roofing.

PRAs Versus Phase I ESAs … Again

PRAs are likely to be more expensive and complicated than a typical Phase I Environment Site Assessment, as more disciplines and, it seems, participants are involved, and the analysis is less commoditized and more dynamic. A critical difference is that Phase 1 Environmental Site Assessments analyze existing conditions, whereas PRAs are, by definition, forward-looking and dynamic. The PRA process involves assessments as to which future-based factors may be subject to dispute or may have incomplete factual basis. The PRA scope implies a more detailed and subjective analysis than is normally encountered in Phase I (or even Phase II) Environmental Site Assessments, which, strictly speaking, do not need to entail risk assessments (e.g., the costs of a cleanup, potential impacts to receptors, etc.), though some may contain statements to this effect.

Impact Going Forward

As climate-related risks continue or are perceived to continue to proliferate and intensify, PRAs could become an important tool for parties to identify and mitigate such risks, and to shift any potentially significant financial consequences associated with such risks. They can also present practical challenges to their use or viability in the marketplace, including cost, timing, and the difficulties of dealing with subjective or future oriented analysis. Thinking about the PRAs contemporaneously with the disastrous wildfires in Los Angeles, our suspicion is that consultancies and engineering firms engaged to prepare such reports will be conservative in their assessments, meaning that they may be more likely to identify and emphasize risks. Moreover, once a PRA is commissioned for a property and disclosed to the owner (or other stakeholder), it may have to be disclosed in subsequent due diligence concerning the same property. This could result in the stigmatization of that property as susceptible to climate risks, which, in turn, could create difficulties with respect to future efforts to divest or lease the property, or to secure financing or insurance for it. Additionally, the proliferation of PRAs could create scenarios in which owners or lessees of a property that has been recently evaluated bring statutory and common law claims against their sellers/lessors for failing to disclose such hazards as “latent defects.” All of this is to state that while PRAs may alleviate certain risks in certain scenarios, they may create them in others. Parties interested in conducting a PRA or consenting to one being performed on property that they own, finance or lease may wish to consider the merits of retaining an attorney to advise with respect to any such study and its potential consequences.

[1] The Standard defines “hazard” as “an event or condition that may cause injury, illness, or death to people or damage to assets.” See Section 3.1.18. The Standard categorizes hazards into five broad categories: 1) extreme temperature, snow and hail (e.g., extreme heat or cold); 2) geologic phenomenon (e.g., earthquakes, landslides, coastal erosion); 3) precipitation (e.g., heavy rainfall or drought); 4) wildfire; and 5) wind (e.g., hurricanes, tornados and severe thunderstorms). See Section 1.3.

[2] The Standard refers to both “acute risk” and “chronic risk.” Acute risk is defined “as those risks arising from event-driven hazards, including increased severity of extreme weather events, such as cyclones, hurricanes, or floods.” See Section 3.1.1. Chronic risk is defined as “physical risks that refer to impacts from longer-term hazard conditions. See Section 3.1.9.

[3] The Standard defines “resilience” as the ability to prepare for anticipated hazards, adapt to changing conditions, to withstand and limit negative impacts due to events, and to return to intended functions/services within a specified time after a disruptive event.” See Section 3.1.28.